The 21st century has brought many things to the fitness industry.

Calorie trackers. HIIT training. Plenty of nutrient scaremongering.

It’s even taken a leaf out of rehab clinics and come up with “detox diets’.

Yet whilst there have been plenty of fads in recent times, never has sport, biomechanics & physiology research been so easily accessible.

Thanks to this golden age of evidence based research, we can finally examine an age old question in critical fashion.

Is there a need for postural specific exercises in a program, and should our training fulfil a “functional” criteria of the body in order to improve the efficiency of movement patterns?

This question crops up time and time again; usually between those who train to look good and those who train to move well. Yet are the lines so black and white?

Let’s take a look at the evidence.

What Is Corrective Exercise?

Firstly, we need to establish what “corrective exercise” actually is, and it’s here that we find our first hurdle.

You see, corrective exercise isn’t an established form of training as such. At least not yet. To add to the equation, there is also no “gold standard” for correct posture or anatomical perfection.

Can we correct something that’s not quantifiable? Although that’s suggestive that we even should be looking to change posture, but more on that later.

Those who do preach and subsequently practice corrective exercise tend to place emphasis on the importance of specific posture control and targeting specific sites of the body to bring about greater overall symmetry, over typical resistance bearing exercise.

Now this doesn’t necessarily mean single leg, blindfolded bosu ball squats instead of deadlifts; but in some cases it’s not far off.

You see the very notion of “corrective exercise” suggests that a particular muscle, joint or movement needs “correcting” in order for the body to perform efficiently. This in a sense, sounds logical.

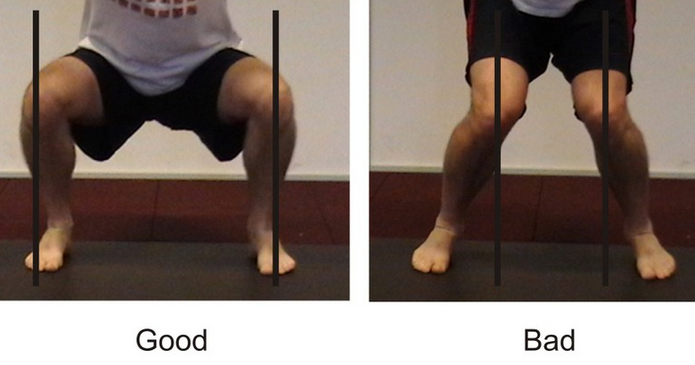

If you inwardly rotate at the hip with excessive knee valgus during a squat – shouldn’t we focus on those potential limiting muscles that are causing the inefficient squatting patterns in hope to rectify the squat?

Maybe. Or maybe we should be increasing our motor learning capacity and working on squatting better, by squatting more.

The Evidence Behind Corrective Exercise

The problem with corrective exercise having no definitive definition, means that there is a serious lack of scientific data and studies available on a “corrective exercise” system. There is however, plenty of research on postural training and “correction” of spinal position.

One study for instance, found that over a 32 week specialised resistance training and stretching cycle, Portuguese adolescents successfully reduced forward head tilt and protraction of the shoulder in static position. (1)

Great! Corrective exercise works, right?

There is however, a small problem. Concluding that postural correction is a true example of a corrective exercise system in practice, would thus suggest corrective exercise needs to be programmed for those who have “poor” posture or are in pain.

That big problem, is that to conclude that static posture is directly related to pain, is far too black and white.

For every study that shows correlation, another two can refute it. In fact a growing body of evidence is beginning to show that movement limitations are a far better indicator of pain. Increasing confidence and strength through muscle and joint ranges of motion, are becoming a successful regime for the reduction of pain.

The above example for instance, shows that the static posture of Portuguese adolescents improved. That is not what is in contention. How this correlates with back/shoulder pain, impingements or more efficient movement patterns is. Several studies have shown that the segmental angles of the spine and position of the scapula do not necessarily make up the origins of pain. (2) (3)

So not only does the seemingly phantom definition of corrective exercise make it impossible to draw conclusions from data; but if we were to associate it with the improvement of static posture, it would still be a heavily contested subject providing limited information on how this translates across to pain free movement. In a sense, this version of corrective exercise would be correcting nothing.

This is of course creates a serious dent in the case for corrective exercise if we were to cross compare with conventional training systems and methods.

The Fine Line

So the need for absolute textbook, static anatomical position might not be high on the list of priorities to you as a lifter, but one thing certainly should be. Mobility.

There’s a fine line between corrective exercise prescription, and regular mobility exercises.

Corrective exercise, to base a definition off the majority of the executions I see, could be the use of specific drills and exercise selection to strengthen a weak or asymmetrical muscle. This in turn should translate across to the desired movement pathway resulting in better movement capacity.

Let’s look at a typical corrective technique to “fix” squat example from earlier.

Corrective exercise might suggest plenty of gluteus medius and vastus medialis work in an attempt to rectify the internal rotation and knee valgus as shown on the right.

After a period of consistent strength work and activation, these stronger muscles would, in theory, support better squatting patterns.

Mobility on the other hand, is focussed on moving through a joints ranges of motion. This in turn can lead to greater movement capacity over time. Although it should be noted that this doesn’t necessarily mean the new ranges of motion will carry newfound stability. All mobility work needs to be complemented with a strength aspect, and vice versa.

So What Should I Do? Corrective Exercise or Mobility?

Which is better? In simple terms. Mobility is a need, corrective exercise in the above sense is a want.

You’re going to need to be both mobile and stable to squat correctly, no matter what your static anatomical positioning is like. Even if your spine is textbook in a standing position, if you can’t extend through your thoracic, squatting is going to be tough.

Secondly, and it’s worth reiterating this, all exercise is corrective when it’s done properly. If your squat sucks, reduce the load and get some coaching through the movement. Exposing your joints to new movement capacity along with the increased motor learning capabilities you’ll gain from continually squatting will improve your “weakness” regardless.

Resistance exercise can be as much a skill as anything – the more often you practice squatting movements, the greater the motor learning capability.

Thirdly, corrective exercises could also potentially be defined as supplementary exercises to compliment a movement pattern. In this sense, exposing the joints to new movement in a controlled manner is only a good thing. So long as the “corrective” work doesn’t overshadow the actual compound lifting.

You could for instance program some activation, correction work or mobility drills during rest intervals; yet it would be foolhardy to base an entire session on them.

Finally, if you’ve got an injury, don’t try to diagnose and correct it yourself. As mentioned, the amount of biomechanics and physiology work available to the public is greater than it’s ever been – but this shouldn’t replace the role of qualified experts.

In short;

Is corrective exercise vital to a program? No, it is not.

Does static, symmetrical posture equate to a pain free, movement efficient body? No, it does not.

Can corrective exercise find a place amongst regular resistance exercise? You bet it can.

Owen is the owner of OHF-Personal Training, a fitness practice based in the city centre of Oxford, England. Using evidence based protocols and tailored training systems, OHF focuses on sustainable, lifestyle changes that go beyond the gym floor.

An Oxford Brookes University graduate, Owen enjoys reading up on exercise science, lifting heavy things and the occasional scoop of Ben & Jerry’s.

Social Media Channel:- www.Facebook.com/OHFTraining

By Owen Henderson

References

- Ruvio, RM. Carita,Al. Pezarat-Correia. (2016) “The effects of training and detraining after an 8 month resistance and stretching training program on forward head and protracted shoulder postures in adolescents: Randomised control study” Manual Therapy. Febuary 2016;21:27-81

- Lewis, J. Green, A. Wright, C. (2005) “Subacromial impingement syndrome: The role of posture and muscle imbalance” Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. July-August. Vol 14, issue 4 Pp 385-392

- Grob, D. Frauenfelder, H. Mannion, A.F. (2007) “The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain” European Spine Journal. May; 16(5): 669-678